“As the sun rose, the imposing mass of Santubong appeared, like a great fortress commanding the entrance to the Sarawak River.” Odoardo Beccari

Santubong is a short, 30km drive from Sarawak’s capital, Kuching, but it is truly out on its own limb. It is, in fact, a peninsula but feels more like an island. The journey there by road, along tree-lined avenues towards a misty mountain in the distance, is the perfect passage of decompression from the hustle of the city to an island pace. There is a moment when you cross the Santubong bridge - the mountains in clear view, the river stretching out to the South China Sea in one direction and hazy Kuching in the other – which is close to like a feeling of flying. Then you know you have arrived.

It is that moment of arrival that has shaped Santubong’s history, especially if you imagine coming at it from the sea on the other side. Take a look at the map and you can clearly see the peninsula jutting out from the coastline into the South China Seas beyond. The trade winds drove traffic through this famous stretch of water, alternately in one direction and then in the other, creating a long line of goods and services from China to India and then on beyond and back again. With its spectacular, magical mountain dominating the view, Santubong was a beacon for every maritime traveller that passed through its space, seeking a safe port for trade and a short stay on shore. For centuries, Santubong has been a gateway to the riches of the rainforest and to a brief period of rest and relaxation from the rigours of travelling and so it remains to this day. Modern tourists can still find the same combination in the peninsula: steeped in history, surrounded by jungle, suffused in seaside calm.

Conquering the Guardian Gunung

It all begins with the mountains, ancient and everlasting. Only one gave its name to the entire peninsula and the river that runs through it, but there are, in fact, two Gunung (mountain in Malay), standing guard on either side. Local legends tell of two sororicidal princesses, Santubong and Sejinjang, a duo who have inspired a famous folksong. Though the details differ in various versions, in most one sister killed the other and the two were transformed into rock as a result, their outlines etched against the landscape for all eternity.

Of the two, Santubong is the most iconic with its languid, listing peak, which makes it easily identified from afar - a welcome sight for seafaring wanderers of old. In fact, many believe this is the source of the name, a transliteration of the Chinese for ‘the mountain visible from a long way off,’ though this remains a subject of widespread debate: some say it is from the Iban word for coffin; yet others claim it is Hakka Chinese for the “home of the king of the jungle pig”, a reference to the proliferation of the porcine delicacy at one time in the forests that still blanket its sides. Unfortunately, the wild boar has fled the peninsula, but plenty of nature populates the National Park that is now the entire mountain and this is where the adventure begins.

So close to Kuching, Santubong is still one of Sarawak’s great ascents. It once attracted the attention of famed Italian Naturalist Odoardo Beccari, who came to Sarawak in the late 1860s on his ‘Wanderings through the Great Forests of Borneo’. Next year sees the centenary of his death and this will be marked by a series of commemorative events in Sarawak. But, any time of year, you can follow in his footsteps seeking the nature that a famed naturalist on a world tour would seek.

He writes of Casuarina trees by the seaside giving way to long-stemmed Lianas and then, as he climbs, the cornucopia of ferns, pitcher plants, rhododendron, epiphytes, mosses, orchids and the list goes on. All these remain to this day, along with monkeys and many bird species, including, occasionally, pairs of hornbill. It is the perfect introduction to the Sarawak rainforest, punctuated as you climb by epic views out over the ocean.

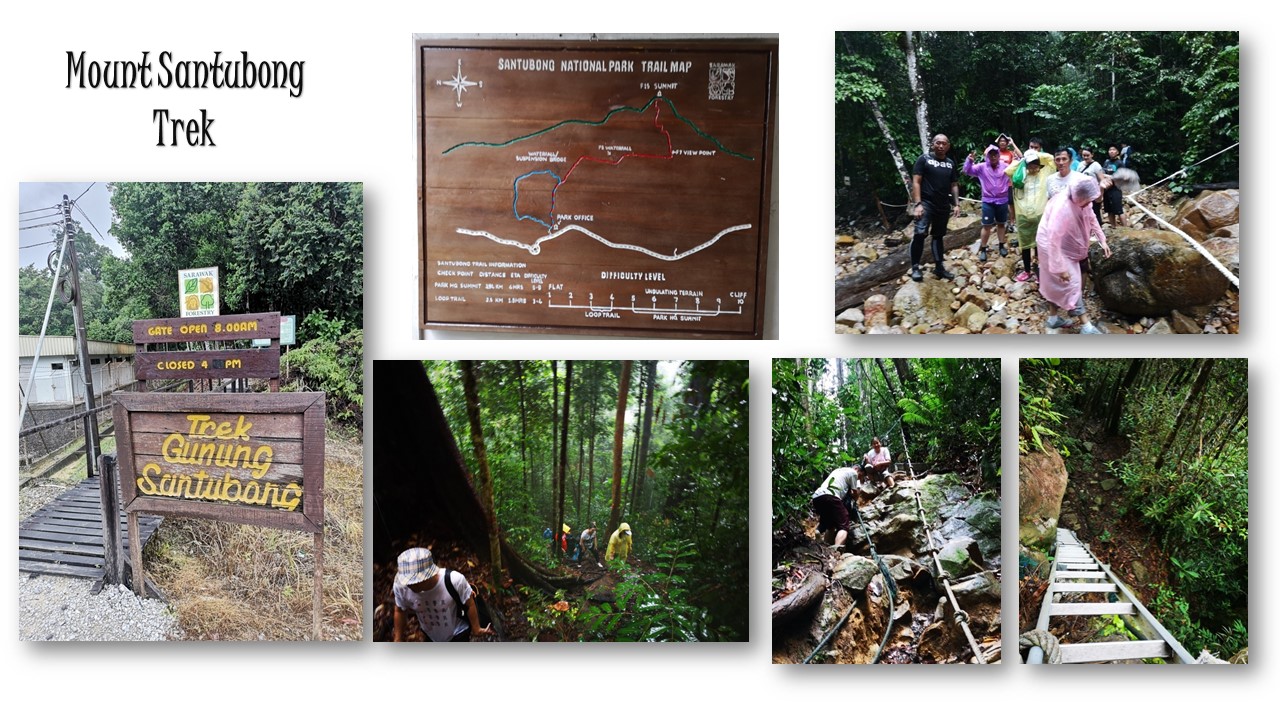

Ignore everything that has been said so far about the slow rhythm of Santubong. The mountain, at 810m tall, is definitely a testing hike. Stay near the base for something simple; unlike in Beccari’s time, the trails are well marked and easy to follow. But if you strike out for the peak, expect an undignified and sweaty scramble. The higher you get, the harder the way, clambering hand and foot over exposed roots, hauling yourself up lengths of rope and, at one stage, a series of vertiginous bamboo ladders that will make you wish you were hooked on. Make it to the top, however, and the rewards are immediately apparent, not least the insane and awe-inspiring view over the South China Sea. Stop off at the waterfall on your way down and your day will be complete.

“To set foot on the top of a mountain is always a pleasant sensation, which various causes doubtless combine to evoke. To the mere climber — whose sole aim is to reach the summit apart from the desire of rest — the attaining of the wished-for goal is perhaps in itself the chief source of joy: the sensation of exultation at having reached the upper dominating regions of the atmosphere, and vanquished Nature which has tied man down to the earth. Or it may be that our gratification is merely the outcome of those ambitious feelings which spur on so many to endeavour to rise above their fellows. But to the naturalist the attainment of the summit of an unexplored mountain is a genuine source of delight, from the hope he ever has of finding species yet unknown…, as if such spots were the last refuge of the remains of an extinct flora. Such mountain tops, arguing from these facts, are, perhaps, the last fragments of an older world of former continents now broken up and in great part destroyed.” Odoardo Beccari on Santubong – Wanderings through the Great Forests of Borneo.

A Naturalist wonders

Of course, Beccari was not the only world-renowned naturalist lured by the magic of the mountain. More famous, perhaps, is Alfred Russel Wallace who spent many long months in Santubong and, more importantly, cemented its place in history by writing his ‘Sarawak Law’ right there on the peninsula. Wallace spent a Sarawak winter in the Rajah’s bungalow in 1855, perched on a hill just above Kampung Santubong, watching migratory birds and wondering about the origin of the species. This prompted him to pen his pivotal essay, supposedly over just three rainy nights, which became part of the passage of thought and simultaneous discovery that eventually became the theory of evolution.

The Rajah’s bungalow itself has not survived. A government rest-house was built on its site, taking advantage of its incredible vantage point. From it, there is a long view of the beach with its collection of magic boulders below (more of them later) and a panoramic view of the ocean, rising immediately up into the mountain behind. From here, it is easy to understand why Santubong is, indeed, a place to wonder at the mysteries of nature. It is the place where the great, green rainforest meets the deep, blue sea under the clear, open skies. So bring your binoculars!

Just like every overseas traveller drawn by dry land, the area is a beacon for birds. The whole Bako Buntal bay area has been designated part of the East Asian–Australasian flyaway site network - a 2,800 hectare area of mudflats, shallow waters and mangroves which attract migratory and shorebirds to feed on marine life as they rest or winter over while en-route during their migratory passage. When you get on the water, on one of the many Santubong River cruises, the usual quarry is Irrawaddy river dolphins that play around the mouth of the river. Scan the mangroves and they might offer up proboscis monkeys, the champion swimmers of the primate world. But wait for night to fall and you will get a glimpse of this monkey’s most feared predator, as torchlight picks out glinting crocodile eyes in the gloom, suffused in the glow from the clouds of flickering fireflies that dart ignored above them. Back on land, a night walk can expose a whole new range of insects, as laden spiders’ webs light up luminous and, if you are very lucky, you might even get to see a flying lemur take a leap and glide.

A Millennium of Migration

Migration in Santubong, however, is not just a story for the birds and visiting botanists. Its history of population stretches back over almost a thousand years, evidenced by the important archaeological finds made all over the peninsula. There are six main archaeological sites, spread across Santubong. The ground at Bukit Maras gave up an indianized Buddha from the Guptama school, while Tanjong Tegok and Tanjong Kubor are commonly held to be cemetery sites, the latter yielding a Chinese coin dated between AD713 - 741. Thousands of ceramic sherds and metal artefacts came out of each, as well as from nearby Sungai Buah, dated to the Tang and mostly Sung dynasties.

But for the archaeologically inclined visitor of the 21st Century, it is Sungai Jaong and Bongkissam which yield the best sights and the greatest stories. Both were excavated in the 1950s and 1960s by Tom Harrisson, then Director of the Sarawak Museum, and Stanley J O’Connor Jr, a visiting researcher from Cornell University. Sungai Jaong, accessed from along the main road, is an amalgam of three materials – rock, iron and clay.

Here, the team unearthed copious ceramic sherds, all everyday Chinese tradeware ceramics from a similar period, alongside heaps of iron slag, still to be seen strewn across the ground. The trenches from the original dig are clearly in view but the real magic begins at a series of makeshift sheds. The first seems unremarkable, a roof over a rock. At each, more geometric shapes appear, etched into each successive stone, until the last great gasp at the Batu Bergambar (the picture rock). On this is the clear figure of a spread-eagled man, turbaned and turned into the rock, all ghostly green from the moss growth of ages. It deserves a brief intake of breath.

Following the archaeological trail, a little further down the main road on the way to Kampung Santubong at Bongkissam, there stands another makeshift shed, this time covering a decidedly nondescript patch of bare earth. But once, this was the site of an enormous shrine of stepped stone, dug into the soil, from which was unearthed an effigy of the goddess Tara, a silver deposit box, and several objects fashioned from precious metal – suns, moons, stars and elephants. The imagination (and the evidence) conjures a person of some standing, erecting this Buddhist Tantric shrine at some time around the 13th Century, as he passed through Santubong on his way. The shrine itself, unfortunately, is lost, spirited away after the archaeological site was abandoned, but its spirit remains.

These finds together, all now in the Sarawak Museum, have set up half a century of debate. Harrisson and O’Connor suggested a settled community of Chinese from the 8th to 13th centuries, smelting the iron slag. But a later researcher has convincingly created a case for local ironworkers drawn by a sprawling, ancient city known in the Chinese history books as Po-ni. This city of some 10,000 inhabitants was so significant that it sent emissaries to China, with tributes in camphor, tortoiseshell and ivory. The exact site of Po-ni remains disputed, but the evidence at least suggests a significant trade entrepôt centred around the Sarawak River delta, drawing in visitors from across the region of almost every descent, searching for the riches of the rainforest in rattan, bird’s nests, beeswax, gutta percha, civet; you name it, they sent it.

Wander around Kampung Santubong today, however, and it is hard to imagine such a bustling metropolis, but enjoy the sleepy Malay fishing village anyway, have a coffee in one of the rickety Chinese wooden shophouses by the waterfront and know that this kind of cultural exchange has been continuing for centuries. This is even more apparent at the Sarawak Cultural Village where every Sarawak group is represented in its gorgeous setting in the shade of the gunung and, once a year, is transformed by the Rainforest World Music Festival into a glorious gathering of world music! Some things in Santubong never change.

Sarawak’s first (and last) Sultan

But, for now, change is afoot in Santubong again. Soon the area will be transformed into an archaeological park, leading tourists through the area’s early history and giving them a glimpse of the peninsula’s unearthed treasures. But Santubong also lays claim to another source of ancient fame: as Sarawak’s first capital and the seat of its one and only Sultan. As the indianized influence in the region passed away, a great Malay Kingdom grew up. History tells that the Sultan of Brunei, faced with an ambitious younger brother - Pengiran Tengah Ibnu Sultan Muhamad Hassan, the second son of the third Sultan of Brunei - vested him with the title of Sultan of Sarawak, simultaneously honouring him and sending him out of the way.

In 1599, the newly anointed Sultan Tengah settled his capital at Santubong, enjoying adventures up and down the coast until his untimely death in 1641 at the cursed crocodile stone (Batu Buaya), killed by a blow from a kris on the beach. He was buried on the peninsula and you can still see his tomb at the mausoleum built over his gravesite. Unsurprisingly, after his death, the Sultan of Brunei felt no pressing need to name a replacement and so Sarawak’s place as a Sultanate came to an abrupt end.

Surveying the beach scene

So we end at the beach, as did Sultan Tengah in slightly more unfortunate circumstances! And no day can end better than on the beach at Santubong, under a great orange Sarawak sky. Take a bit of time to visit the magic boulders, as mentioned earlier. Many of these are living legends, believed to be Batu Hidup (living stones), formed not carved, and able to transform at will into the object of their appearance. The Batu Buaya takes the role of the villain in the histories of Datu Merpati Jepang, the legendary leader of the Sarawak Malays who claimed familial ties across several Sultanates from Johor to Sambas. Once, the stories say, when Santubong was attacked by a crocodile army, Datu Merpati took them on, cleaving the head of the crocodile king from his body.

It landed on Pantai Puteri at the mouth of the Santubong River where it was petrified into the stone that can be seen today.

But for centuries, it has been at peace, as has the rest of the Santubong peninsula. So much so that the modern visitor can take a rest at Damai beach (literally Peace Beach) nearby, enjoying a cold drink after a round of golf or a soothing swim in the pool. Perhaps you can take yourself down to Buntal village and be like the birds, feasting on marine life as you take in a well-earned rest on your route. After all, the slow pace of Santubong today is the stuff that holidays are made of: the long expanse of time; the ebb and flow of the seaside; the occasional adventure on a magical mountain; in short, the making of myth and legend.